Robot boosts blueberry picking efficiencies

Michael Back and his son Simon, owners of the Backsberg wine estate between Paarl and Franschhoek in the Western Cape, had a problem at blueberry harvest time: their pickers were having to walk up to 150m to and from quality-control centres to deliver the fruit.

The inefficiency of the system was obvious, so the Backs set out to find a way of reducing walking time and increasing the hours dedicated to picking and sorting.

Simon explains that they didn’t want to use tractors, as their orchard rows are narrow (2m to 2,5m depending on the variety), and tractors would have to move past farmworkers, whose numbers grow to over 300 in peak season from August to November.

Aside from this, tractors are heavy on fuel, have a high carbon footprint, increase the risk of compaction, and require drivers.

“We were looking for a conveyer-like solution onto which workers could place their buckets [of fruit] right where they were working. My father then came up with the idea of having a robotic carrier platform that automatically followed picking teams up and down rows to collect and deliver their buckets to the quality-control centres,” says Simon.

Carl Malherbe, one of their farm managers, suggested that the Backs consult electronics engineer Cobus Meyer to help them develop this solution. Meyer in turn approached Chris von Wielligh, a fellow electronics engineer, to assist him with this challenge.

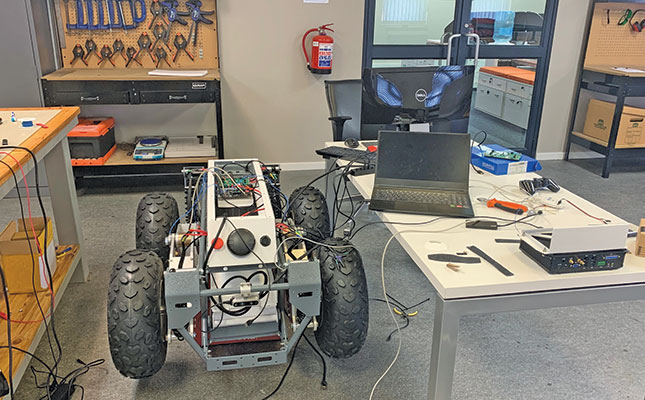

Cobus, Chris, Michael and Simon have since founded ARCi Technologies, and have developed what can probably be considered South Africa’s first semi-autonomous agricultural robot, ARCi. The name is derived from the term ‘agricultural robotic carrier’, and is pronounced ‘Archee’ to give the machine some personality.

The first two prototypes

The original model was an old remote-controlled car from Cobus’s childhood, which they retrofitted with an inexpensive camera to test the first version of their autonomous guidance technology.

“We wanted to prove that we could implement a basic autonomous system with inexpensive parts that could guide our car down an orchard row,” he says.

The results were promising, and led to the development of their second prototype, which they tested during the Backs’ 2020 picking season. This machine, substantially larger than the first, was able to carry four picking crates in one layer, as well as advanced camera technology to improve the accuracy of the autonomous guidance system.

“The second prototype has been highly successful in navigating between the rows in orchards, with no accidents or injuries. Nevertheless, work is still needed to improve navigation once the robot leaves the rows, and we’re addressing this with our pre-commercial [third] prototype. Outside of the rows, we use a combination of high-accuracy GPS, wheel sensors and machine-learning technology to help us safely traverse the unknown environments,” explains Cobus.

The robot is considered semi-autonomous, as it cannot transport itself between orchards and to the battery charging station. The pre-commercial version weighs around 100kg, and is 1,2m long, 0,9m wide and about 0,8m high.

According to Simon, workers were apprehensive about the robot at first, but soon realised that it was there to help and not replace them.

“Berry orchards have to be harvested multiple times to ensure the fruit is picked at optimal ripeness. Our workers receive a base salary, and bonuses are linked to productivity, so the robot allows them to increase their earnings by giving them more time to pick berries instead of having to walk [to and from the quality-control centre]. This, in turn, has a positive impact on farm income, as it results in better and higher packouts,” says Simon.

Workers interact with the robot via a simple three-button interface located on either side of it. They can stop the robot and send it forwards or backwards on its route.

Challenges and upgrades

During testing, the second prototype occasionally lost its way, but this was usually where plant rows did not conform to the conventional layout; for example, when more than two neighbouring plants were missing from a row.

According to Michael, however, this is not a significant hiccup, as these plants should, in any case, be replaced. He advises farmers who are thinking of using robotics to design their orchards so that the machine can move easily.

“While the terrain can be undulating, it shouldn’t be overgrown with grasses that may obstruct [the robot’s] sensors, nor should it be full of holes that may impair the machine’s movement.”

Another challenge was to find a way to identify the pickers’ yields after they had delivered their berries. This was resolved by attaching a weight scanner to the robot; the workers scan each bucket upon delivery for identification purposes.

“This wasn’t a major change, as the [weight scanning] function was merely moved from the quality-control centre to the robot,” says Simon.

While no injuries or plant damage were suffered during the test, a few buckets of berries were sacrificed in the pursuit of innovation.

Cobus explains that, during the trials, the robot’s platform was fitted with a number of racks to increase the volume of berries it could carry per load.

“We managed to carry loads of up to 70kg before running into stability problems caused by poor weight distribution and mechanical design. The robot is [actually] capable of carrying much more [than that].”

The robot also carried empty buckets for which the workers exchanged full ones so that they didn’t have to walk far to do so.

The company’s third prototype, or the pre-commercial version, is a significant step up from the second prototype. It not only carries more advanced technology, but also has a lower centre of gravity and is much more robust than the previous model, making it less prone to toppling over under the weight of a heavy load.

In addition, it has been fitted with bigger wheels to prevent it slipping or getting stuck in wet or uneven terrain, and has a touchscreen user interface to provide trained operators with a more in-depth view of the machine’s status, including battery level.

The robot is electrically driven, with the second prototype able to work for up to two days before its battery needs recharging.

“The ideal would be for the robot to be recharged with a renewable energy source, such as solar, wind or hydropower, which would help to reduce the carbon footprint of a farm,” says Cobus.

The majority of the robot’s electronic components have to be imported, unfortunately, but the body and most mechanical parts are locally manufactured, and the company is trying to design the machine in such a way that it would be easy for an on-farm mechanic to repair it, or quickly swap out its major components when something breaks. This, according to Cobus, will reduce down times with the commercial version.

Future applications

ARCi Technologies will host a field day in November to showcase the pre-commercial prototype.

“We hope to generate interest and get some orders in to accelerate the commercialisation of the product,” says Cobus.

While the initial design is aimed at blueberry production, the machine should also work well for other labour-intensive crops, such as table grapes and strawberries. In addition, the company has already received inquiries from the security and aviation industries about whether the technology could be adapted for their purposes.

As the robot is modular, it can be adapted for use with other applications. According to Michael, it could be fitted with sensors that, when combined with the right software, could help with the identification of stressed patches in orchards that might be linked to disease or irrigation and fertiliser problems.

“The beauty of ARCi is that it can be used under shade nets and in tunnels, unlike drones and satellite imagery,” he adds.

Sensor technology could also be used to count flowers and evaluate the ripeness of fruit, which would result in better labour-planning, as it would allow farmers to see how many pickers they would need at any given time. It would also aid the marketing of fruit by increasing [the data on] volumes that can be delivered at specific times.

In addition, ARCi could be fitted with spray equipment to help with pest management, or with an ultraviolet light for a more environmentally friendly way of managing pests and diseases.

Simon says that ARCi is not aimed at replacing farmworkers, but rather at helping to improve their efficiencies. “Globally, farm labour is becoming increasingly scarce, and the same is likely to happen in South Africa as people find more attractive jobs. The agritech wave is upon us, and we can either ride that wave and remain competitive, or be crushed by it.”

Email Cobus Meyer at cobus@arcitechnologies.com, or visit arcitechnologies.com.

Source: farmersweekly.co.za